I can’t take full credit for this one. I was inspired by a friend from college who goes by

. He has his own Substack, Hangnail’s Hollers. He writes about the blues and writes about them very well—embodying a wealth of knowledge and a deep love for the music. One of the best parts of his Substack is that it links the genre to our national subconscious, our lingua franca, our human moment. We all have a blues bone somewhere, and Hangnail Hollers helps us tap into it—that 12 bar chord that churns something subterranean, a music that is at once painful and healing. I recommend subscribing.Hangnail Slim also happens to be a James Bond fan. In his most recent post, he writes about Bond:

“Before I knew much about history and politics, Bond taught me about the Cold War, NATO, the British Empire, and more. Before I had a computer, an iPod, a car with digital features, there was Bond and his gadgets. For me, the world of Bond’s always been where it’s at.”

A man after my own heart.

And like a pro, Hangnail Slim marries Bond and the blues—finding the overlap in the swashbuckling survivors, piratical charm, and gritty adventure.

“Come to think of it, blues is a lot like Bond. Sex and violence galore, plenty of villains (Eddie Taylor could have taught Goldfinger a thing or two about being a bad boy, Howlin’ Wolf could be scarier than any metal-toothed henchman), and gritty heroism in the face of overwhelming odds. The bluesman, like Bond, is a survivor. He may not save the day, but he generally lives to fight another one. There he is dodging the law, the aggrieved lover, the high water rising, the existential heaviness of the lonely midnight hour.”

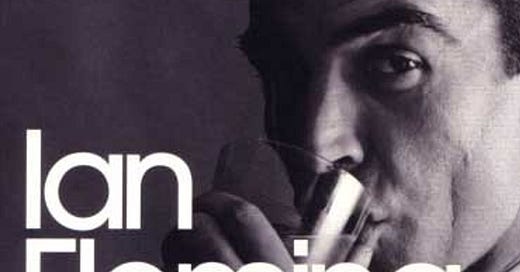

I was also fed and watered on Ian Fleming’s books and the movies born off of them. Bond was the complete package: the British spy’s omnipotent cool and quip; the Churchillian irascibility of his superiors; the villainous camp of the enemy; the parade of impossibly gorgeous women, and perhaps the most consistently fantastic original music ever ascribed to an action movie. The best movies draw out chills, wry, rewarding smiles, and that kind of primeval excitement that first bubbled up when I was a kid. Bond’s history as an orphan and the liquor-addled loneliness has also grown on me as I got older, seeing him as not immune to the cold mandate of his work or the heaviness of years. James Bond may not be everyone’s favorite (he’d be a cancelled, bullying, drunken wreck if he was a real guy) but, like the blues, he brings something for everyone.

The Broccoli family deserves a salute for that. First led by Queens-born film producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli then by his kids, the Broccoli family stood at the helm of 27 Bond films (all but essentially one) for over 60 years, ably steering the superspy juggernaut out of one decade and fresh into the next. Although not all the films were great (some are honestly bad), I’d hazard that the James Bond filmography is widely accepted as transcendent because of the Broccoli’s restraint, their pliancy, and their commitment to Bond’s ethos as the world changed. And as Hangnail Slim mentions, sure, money was always the object. Just like the bluesmen and their producers, the money drove the art and fueled the need for more—sometimes for worse. But the Broccolis still delivered, shedding some of Bond’s more dated baggage as he aged while still retaining his heart and soul.

This year, Amazon bought 007 from the Broccoli family for about one billion dollars. The sale effectively lowers the tuxedoed icon, lashed to a great chain, into that sadly familiar tank that has disfigured so many good movie franchises and book series into poorly written, small screen shows. Unless brilliant, brave minds intervene, Bond will likely become just another multi-million dollar Frankenstein with all the vim of a glass of tepid milk.

So I’m jumping on the bandwagon with Slim: it’s a good moment to salute the passing of Bond into a new and murky future.

I am doing that here with a plug for a classic: From Russia with Love (1953). This is my favorite of the Bonds. If the screen version conveys a visual magic hard to find elsewhere, the book’s slow churn and sexy simplicity makes it an equally awesome read. I love the Bond in From Russia with Love because of his relative ordinariness. Fleming, a smoker of two-and-half packs a day and a self-described nymphomaniac, instills in his book-bound hero not necessarily a mediocrity but at least a ceiling for his abilities. This Bond is fallible, vain, prone to doubt and exasperation, not above relying on a little luck, and happy to let the cavalry to get him out of a scrape. In this way one is able to relate, and like the best spy thrillers, slide into the hero’s shoes.

Kingsley Amis’ conversational gem The James Bond Dossier (1965) lays bare the books’ many qualities, but this one in particular:

“Mr. Fleming is careful to make Bond’s achievements and abilities seem moderate: moderate on the heroic secret-agent scale, naturally. Bond can swim two miles without tiring, perhaps much more, but he has only to manage three hundred yards from shore to Mr. Big’s island. Underwater, Bond is pretty useful with spear and CO2 gun, but Emilio Largo is better, and Bond only survives through the intervention of Largo’s renegade girl. Bond is a fine skier, and has won his golden K, whatever that is, but Blofeld’s men are professionals and nearly catch him. Bond loves cars and drives them well and at speed, but he never did more than dabble on the fringe of the racing world. Bond can throw knives and can do unarmed combat as well as shoot, certainly, but after all the fellow is a secret agent. If we were in the OO Section we would have learned all that as a matter of course. The number and variety of Bond’s useful skills may be fantastic, but each seems reasonable while we’re hearing about it.”

This is the Bond who learns of a beautiful Russian cipher clerk, Tatiana Romanova, who has signaled to the West that she wants to defect—bringing along with her a Spektor, a prized Soviet decoding machine. In exchange, she wants Bond, a man she has never met, to marry and love her. The conceit is ludicrously romantic, far-fetched, too good to be true—and likely a trap. Bond and his indomitable boss “M” guess this, but their sporting English nature prevents them from turning down a challenge. Romanova’s impassioned proposal is indeed a trap—orchestrated by the ruthless Soviet counterintelligence agency SMERSH—to kill 007 and humiliate the British Secret Service.

From Russia’s plot might seem humdrum compared to the later space guns and nanobots, but again, that’s what makes it so readable. The plot takes time to formulate, the Soviet masterminds assembling in a dour, shady Moscow to lay the groundwork for Bond's murder. Red Grant, the chosen assassin, has a terrifying backstory (he and Halloween’s Michael Myers could have been twins). The plan’s progenitors, a chess prodigy named Kronsteen and the head of SMERSH operations, Colonel Rosa Klebb, are ghoulish geniuses whose disregard for human life would make Stalin blush.

By the time the book turns to Bond, who is en route to Istanbul to meet Romanova, you are a little worried about him. His narrative is as much about his eating and drinking habits, his innate knowledge of city haunts, and his sharp eye for clothes as it is about the mission. And yet Bond’s first impressions and subsequent gut instincts of potential allies and foes—sketching out their history and determining their authenticity—remains one of his most potent strengths. At one point, he meets a fellow British agent, Captain Nash, who has appeared to help Bond protect an asset:

“The man had taken off his mackintosh. He was wearing an old reddish-brown tweed coat with his flannel trousers, a pale yellow Viyella summer shirt, and the dark blue and maroon zig-zagged tie of the Royal Artillery. It was tied with a Windsor knot. Bond mistrusted anyone who tied his tie with a Windsor knot. It showed too much vanity. It was often the mark of a cad. Bond decided to forget his prejudice. A gold signet ring with an indecipherable crest, glinted on the little finger of his right hand that gripped the guard rail. The corner of a red bandana flopped out of the breast pocket of the man’s coat. On his left wrist there was a battered silver wrist watch with an old leather strap…his eyes looked rather mad.”

There is a pulse-pounding, creepy simplicity in the journey to Istanbul and back across Europe aboard the Orient Express. The finale is perfect.

At the end of nearly every James Bond film, rolling up at the end of the credits, there is the emblazoned reassurance “James Bond Will Return.” Like Hangnail Slim said, Bond, like the bluesman, is a survivor. He may be bought, but he already belongs to us.